Listening to Syeda X

Neha Dixit's 'The Many Lives of Syeda X' is an important, revelatory book. Why is it such a frustrating read?

One communal riot is all it takes to spit Syeda – the protagonist of The Many Lives of Syeda X – and her family out of Banaras and into the punishing life of the Delhi underclass.

But this is not only a book about how Hindu fundamentalism devastates Muslim lives.

Journalist Nexa Dixit’s reportage casts a wider net. It looks at the other oppressions that pin the poor to powerlessness – in this case, the informal economy that is ruthless in its exploitation of the labour of women like Syeda.

Eighty million Indian women earn some income by doing home-based work – and till a few years ago, the Indian state did not even consider them as workers, though their work is crucial to the wealth created by small and medium-scale industries.

For over nine years, Dixit paid rare, meticulous attention to the lives of these women workers, who are invisible to the state (and many of us) because they are poor, disadvantaged and women. The result is a revelatory book.

Between 1992 and 2024, between the demolition of a mosque and a discriminatory citizenship law, the whiplash of Hindu resentment and victimhood transforms the country.

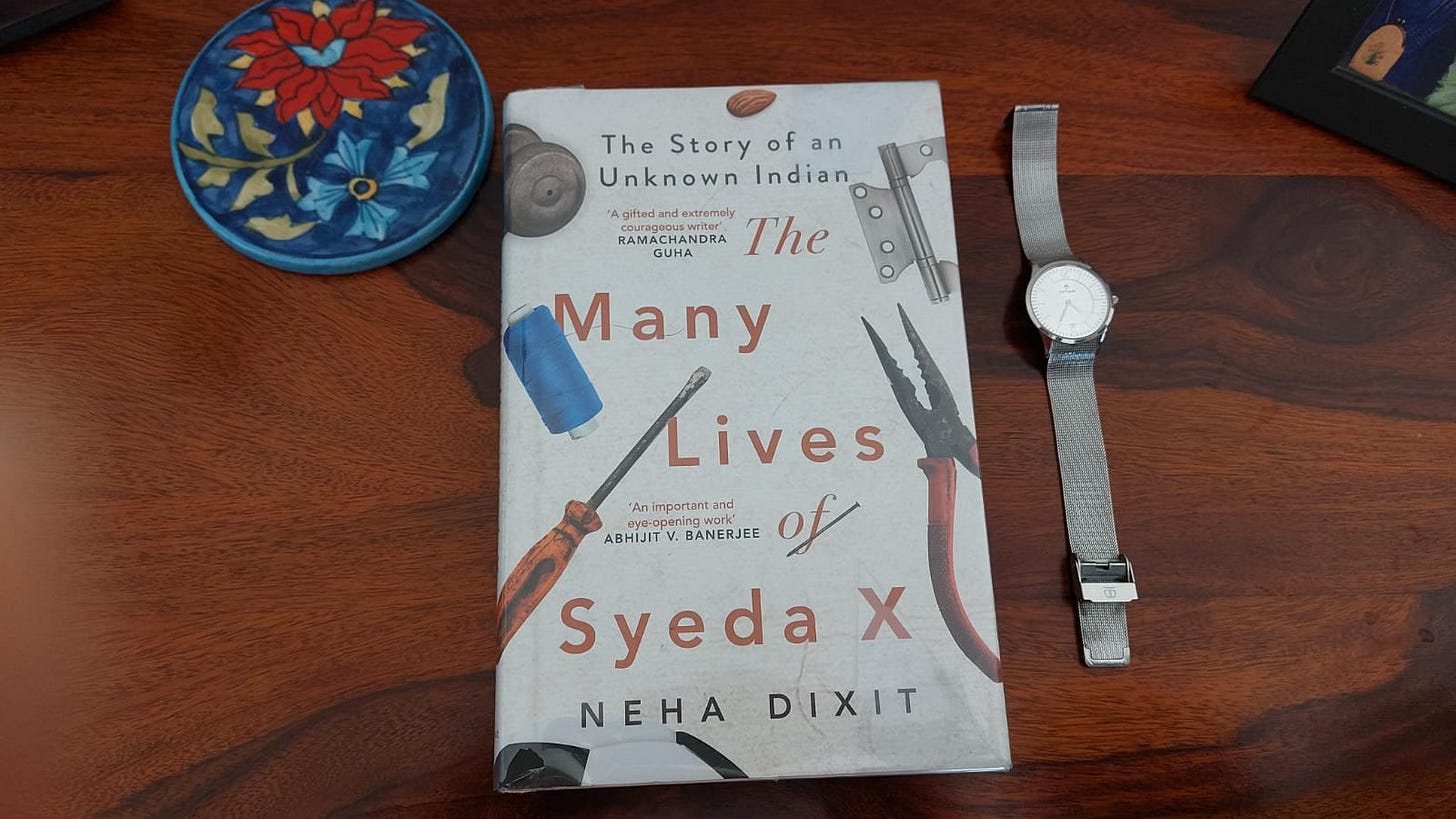

In these three decades, Syeda X runs through 50 precarious ‘jobs’ as she struggles to keep the family afloat. She has no training, nor tools, forget a contract. Working in dingy homes or in sweatshops, for wages far below the minimum, she shells almonds soaked in acid, removes stems from raisins, fixes nets to tea strainers, turns fabric into footballs, sticks bindis on paper or makes door hinges – over 12 hours of daily work often fetching less than Rs 2,000 a month.

If ever there was an indictment of the India ‘growth story’ and its failure to provide hard-working Indians a life of dignity, you will find it in the pages of this book.

There is also evidence of the consequences for the poor when public priorities are driven by elite concerns to the exclusion of others. When courts shut down polluting factories, the poor lose jobs – and are expelled further into the urban netherworld, as Syeda is. But their difficulties do not register even as a blip on the radar of journalism and policymaking.

The apocalyptic smog in Delhi was in the news, as I read the book, where Syeda’s daughter Reshma dismisses concerns over pollution as elitist. It’s not a popular view. But what if the affluent had to send our children to government schools, and live in homes without air purifiers? Would the discourse on pollution then factor in the harm done to children in shutting down schools for weeks?

What if we had paid attention, as Dixit does, to those trapped inside an iron box of low-paying, back-busting and deadening labour? Would conversations about women’s freedom be about worker rights and job security and not just the glass ceiling that holds back successful (and inevitably upper-caste/class) women?

The Many Lives of Syeda X is an important book because it allows those questions to break through the elitist bubbles in which its readers live.

And yet, I found this a frustrating book to read.

A book that aims to centre the life of a woman – someone who has led an incredibly hard life – only makes you feel sporadically for her as a person

The reportage is let down by the writing, which is often dull and littered with journalese. There are long passages that sum up events of contemporary Indian history without any new insight. I skipped most of them.

But the most striking flaw is its lack of attention to structure – its determined disavowal of any style.

There are odd narrative choices – news headlines are interspersed through the book, without telling us how they are related to the story. There is also a generous sprinkling of Hindi and Urdu poetry, which is so much at odds with the unvarnished narrative, that it fails to hide the striking absence of interiority in this account of Syeda’s life.

And so, a book that aims to centre the life of a woman – someone who has led an incredibly hard life – only makes you feel sporadically for her as a person. As a reader, I struggle to come up with a vivid image of Syeda, or even hear her voice in any distinct way.

Some of it could be blamed on the choice of narrative voice, which is flat and omniscient and above the fray. Dixit struggles to square Syeda, the worker in an exploitative economy, with the woman enmeshed in many complex relationships. The mother who favours her sons over the hard-working daughter, or is disappointed with her son’s life choices. [The one character that leaps out of the book is Reshma, Syeda’s daughter. The mother-daughter conflict is an unlit spark.]

The first-person narration often degenerates into self-indulgence but I wondered if, in this case – by laying bare the distance between the narrator and the narrated – Dixit could have given us a better, more vivid glimpse of Syeda.

This is Indian non-fiction in English’s moment in the sun – and, it’s fair to say, that they are often more compelling than much of literary fiction. Many writers are turning to non-fiction to do what journalism ought to be doing – drawing attention to urgent questions of inequality and violence. But there is a rawness and lack of finesse in many acclaimed works that have left me disappointed, and that perhaps could have been rescued by that underrated craftsperson – the editor.